Wojtek the Soldier Bear

I love my country and I know what homesickness is…

You are one of WW2 survivors. Could you tell us about life during WW2, please?

When World War the second began I was a four-year-old child. We lived in a big forest in Białowieża Forest in Żakowszczyzna settlement, because my dad was a gamekeeper.

A lot from those days I only remember because my parents told me, but the deportation on 10th February 1940 I remember very well.

At night I woke up and I saw strangers and my parents walking in the house. I started to cry – my Mum was calming me down and told me we were going to visit my grandma.

A Soviet soldier came to me and gave me a biscuit – it wasn’t tasty at all. I still remember the taste – it tasted like caraway and it wasn’t sweet.

What else do you remember?

We were going by a horse-drawn carriage with all the things my parents had been able to take in a hurry. It was a winter morning. The carriage was followed by a woman, she was shouting something. Now I know it was my Godmother and she wanted to say goodbye. The carter didn’t stop…

What happened next ?

We were taken to a railway station where we saw wooden cattle cars. We were put into the wagons.

Every wagon was locked and guarded by two Soviet soldiers with rifles in their hands. I remember there was a small iron stove in the wagon but I do not remember whether there was any fuel… In the corner of the wagon there was a round hole – a toilet for all the ‘passengers’… It was terrible.

While we were going and going my Mum was hugging me and covering with anything possible to make me feel warm. The train was going and going for days and nights…

Do you remember where you reached?

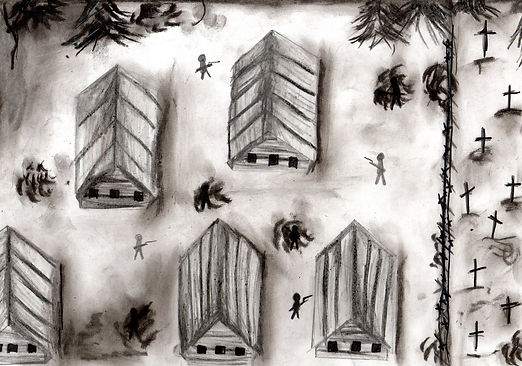

There were wooden barracks outside in the countryside near a cemetery. Not far away there was a NKVD station. When Polish people were saying that after the war they would come back to Poland, the Russians pointed to the cemetery and said: ‘Your Poland is there’.

Because of homesickness sometimes in the evening somebody behind the barracks sang ‘Poland is not yet lost, as long as we live…’ As soon as the Russians found out about it, they started to look for the one who had dared to sing the Polish national anthem.

Do you know where you were?

Yes, we were in Karabash not far from Czelyabinsk. My father and my older sister (she was 17 then) had to work in the iron ore mine, where there was water up to their ankles all the time.

The conditions were terrible. The worst were the night shifts – they (my dad and sister) couldn’t be late. My Mum didn’t sleep to wake them up on time. My second sister had to work in a canteen. She was fourteen then. She was made to learn and speak Russian but she refused. That’s why she had to work.

What happened later?

When Władysław Sikorski in 1941 after Germany invaded the Soviet Union, started negotiations with Stalin about a common fight against Germany, we were moved to Kazakhstan to work in a kolkhoz in a village called Bratskoye. I still remember the name of the railway station: Burnoye. My father and sisters worked in the kolkhoz in the field. The deported families were staying with local families, it means with Russians or Kazakhs. After some time we had to move to another family, because the Soviets were afraid people could make friends.

There were some Chechen families, who were treated extremely badly. They were starving almost all the time, they even weren’t allowed to work in the kolkhoz. I remember one Chechen was carrying his children, who had starved to death, in a sack to the cemetery…

It is really difficult to describe how we were starving every day, how we were doing our best to get something to eat…

The situation changed when the front came near Stalingrad. My father was taken to Karaganda (Central Asia) to work in a coal mine. We received some letters from him. He wrote that he was starving. In the photo we saw he was swollen because of the food shortage. He survived thanks to a Russian doctor. She helped him which wasn’t easy and popular then.

We met my father after the war in Poznań. We returned to Poland in spring 1946. We couldn’t return to our house as it was already in the USSR territory. That is why we decided to go to the west part of postwar Poland. Our train stopped in Poznań for over a dozen days. My older sister found out that a train with Polish workers from Karaganda was going to come to Poznań. We met our father! How happy we all were! We were crying and enjoying the moment…

I remember the end war of war. My Mum went to an office, the office was closed – 9th May 1945, Germany signed the capitulation!

When we were in Soviet enslavement I used to ask my Mum whether there were trees and flowers in Poland. My Mum answered there are beautiful trees and flowers, the meadows are full of colourful flowers and in the forests, where the wind whispers through the trees, there are billberries, mushrooms and amazing singing birds…

How did you return to Poland?

Our way back to Poland was very difficult. It was spring 1946. I remember while we were crossing a river the carriage was carried away by the water. We were crying, because we were afraid we were going to sink. Fortunately we managed to reach the bank. We crossed the Soviet-Polish border on Wet Monday (the second day of Easter). I remember, the train stopped not far from a river. We celebrated Wet Monday on the river. That was the day when from the train window I saw churches, with people dressed in smart clothes going to them. I was dreaming about my own beautiful dresses and I was sure everything was going to be great in Poland.

I love my country and I know what being homesick is, because I have experienced it.

Interview with her grandmother Maria Jamrozik run by Ada

Drawings by Martyna Cudzik, 12